Pay to Drive: Navigating the Subscription Car

It’s a familiar pattern in the consumer market: once a popular product achieves widespread adoption and its manufacturing processes standardize, it inevitably moves toward commoditization.

As this happens, the product becomes cheaper, the differences between competing brands diminish, and profit margins shrink. To compensate, companies pivot. They create new revenue streams centered not on the product itself, but on associated services and subscriptions.

I believe this exact process is already unfolding in the automotive industry, particularly with electric vehicles (EVs). Let’s look at a few examples from other sectors to illustrate this trend.

Home and Office Printers

The home and office printer market is a classic case of commoditization. Most brands offer similar functionality, and within any given price tier, the core product is essentially a commodity.

To maintain profitability, manufacturers took a drastic step: they began selling printers at or even below cost. Their true revenue comes from selling proprietary ink and toner cartridges at high prices, often through subscription models. By locking customers into their brand for consumables, they established a steady, predictable revenue stream that more than compensates for the initial loss on the device.

Network Switches

The enterprise networking industry also faced this challenge. Companies used to compete by designing custom hardware, such as ASICs (Application-Specific Integrated Circuits), to offer the best link speed, port density, or packet processing capabilities. This required massive, continuous investment in bespoke hardware development.

The landscape changed when a company like Broadcom introduced a powerful, commercially available ASIC that offered superior core functionality. Switch manufacturers quickly adopted this standardized, high-performance chip to stay competitive. As a result, the hardware differences leveled out and margins fell. The new solution? Companies started charging for the software running the switches, offering subscriptions for updates and new feature layers (like advanced network protocols) that could be enabled for an additional fee. The value shifted entirely from the physical box to the code inside it.

The Coming Commoditization of the EV Market

Now, let’s apply this framework to the car market, focusing on EVs.

When you look at modern electric cars, a wide array of high-tech features are standard across nearly all brands and models: a complex infotainment center, remote access, keyless ignition, advanced driver aids (like assisted steering and braking), and more.

Once a buyer selects a car segment, the main differentiators often boil down to price and range. While exterior design still plays a role, the primary factors driving consumer choice are becoming increasingly standardized.

The technology for batteries is rapidly improving and will soon stabilize around designs that offer sufficient range for the vast majority of consumers. Since the battery is the single most expensive component of an EV (accounting for 25–30% of the cost), a standardized battery model will inevitably lead to a leveling of prices within each car segment. And, just like in the printer and network switch markets, we arrive at the same outcome: low margins.

The Solution: Software-Defined Services

Car companies know they must find a new source of revenue, and the solution is clear: services and subscriptions.

The consoles in modern EVs are essentially sophisticated, customized computers. They run software that controls the car’s functions, manages the user interface, and supports apps. The strategy is to leverage this platform to enable functionalities on demand through subscription models.

We already see the initial steps: fees for cellular network connectivity and an additional cost to activate in-car Wi-Fi.

Future services—many of which are already being implemented—could include:

Feature Activation: Charging a recurring fee to activate internal features like heated seats, heated steering wheels, or remote start—even though the hardware is already installed in the car.

Convenience & Maintenance: Subscription-based car service monitoring that proactively schedules maintenance. Coupled with an Autonomous Driving subscription, the car could even drive itself round-trip to the service center while the owner remains at home.

Enhanced Capability: Autonomous Driving functionality itself is a premium subscription. This could enable services like having the car find its own parking spot after dropping off a passenger and then being recalled on demand.

Digital Content: Fees for newer, updated maps for the navigation system, or an embedded entertainment center that leverages subscriptions and targets consumers with ads.

Beyond the car's core functions, app extensions offer another layer of revenue. For instance, an app could connect the car to your Smart Home system to display appliance status or forward a security camera feed—all for a fee. Payment apps could also handle tolls, parking, and charging station fees, with the car company collecting a service fee from the original provider.

This software-centric model also offers cost savings for manufacturers. Similar to how today some motorcycle makers use the same engine across different models and use software to limit the lower-end model’s power output, car companies could standardize the electric motor across various models.

They could then define the upper performance limit via software, offering customers the option to “upgrade” to the next performance class for an additional fee. This would reduce the number of unique physical parts, lower manufacturing costs, and create a lucrative software-based upgrade path.

The sky is the limit, and many are already reaching for it.

A New Era of Automotive Engineering

This shift is requiring a significant internal transformation for carmakers. They need to move from focusing on mechanical engineering to designing sophisticated software platforms.

This means creating a single, portable software architecture that can be easily customized across different car models, maintaining version control, and establishing a robust distribution channel for post-sale support (security patches, bug fixes, and feature upgrades).

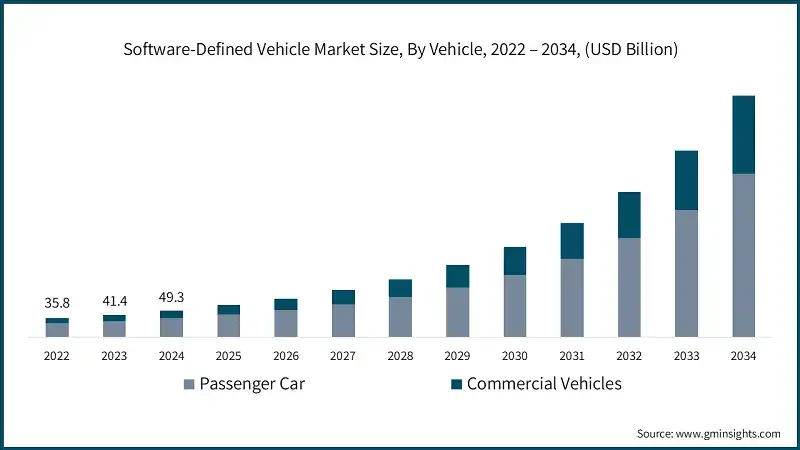

Technology providers like Amazon (AWS), Bosch, and IBM are already building these "Software-Defined Vehicle" platforms to support manufacturers in this transition.

Car companies are already betting big on this vision of the future, as you can see in this article.

Public projections of revenue from software and services underscore the scale of this shift:

GM aims for services revenue to reach $25 billion by 2030.

Stellantis projects $22.5 billion in incremental revenues from software services by 2030.

Tesla’s subscriptions and software sales could account for up to 20% of its total revenues by 2030.

The Challenge for the Consumer

A fundamental shift is underway in the EV market, and consumers need to adapt their purchasing criteria.

Base car prices will eventually level within each class, and brand differentiation will be defined by the available services. Buyers will need to learn to calculate the actual running cost by adding up all the necessary and desired subscription fees.

For the average customer, this is not an easy skill. Ignoring these new data points can lead to a nasty surprise after the purchase when they realize an extra budget is required to access the functionality they want or need.

Technology, which is supposed to simplify our lives, risks making the seemingly simple task of choosing a car incredibly complex.

To navigate this complexity, many consumers will turn to new tools, perhaps AI-powered decision-support systems, to help them choose the right vehicle package. While this offers a tempting shortcut to escape complexity, it also introduces a cost: reducing our personal freedom to independently evaluate and decide what we truly need.

We often assert that AI tools should remain supportive, leaving the ultimate decision in our hands.

Yet, as the decisions that are necessary in even the most mundane aspects of our lives become more complex, delegating these decisions—about what we buy, read, or eat—becomes an attractive means of escaping the calculated overwhelm of choice.

This begs a critical question: as the value in consumer products shifts from hardware to software and services, and our choices become increasingly opaque, how do we protect our right to choose and maintain control over our purchasing decisions?

I have no answer to offer you, but I feel that it will become one of the most pivotal questions of our time, so we better start thinking about it.