Bubble or Business Model? Following the Money in the GPU Arms Race

In my article last April, I touched upon the world of datacenters and their growing importance amid the Artificial Intelligence boom. You can read it here.

Today, I want to revisit this topic from a different angle, specifically in light of the numerous articles and commentaries that have surfaced recently suggesting a potential "AI bubble".

The Suspicious Financial Loops Fueling the "Bubble" Talk

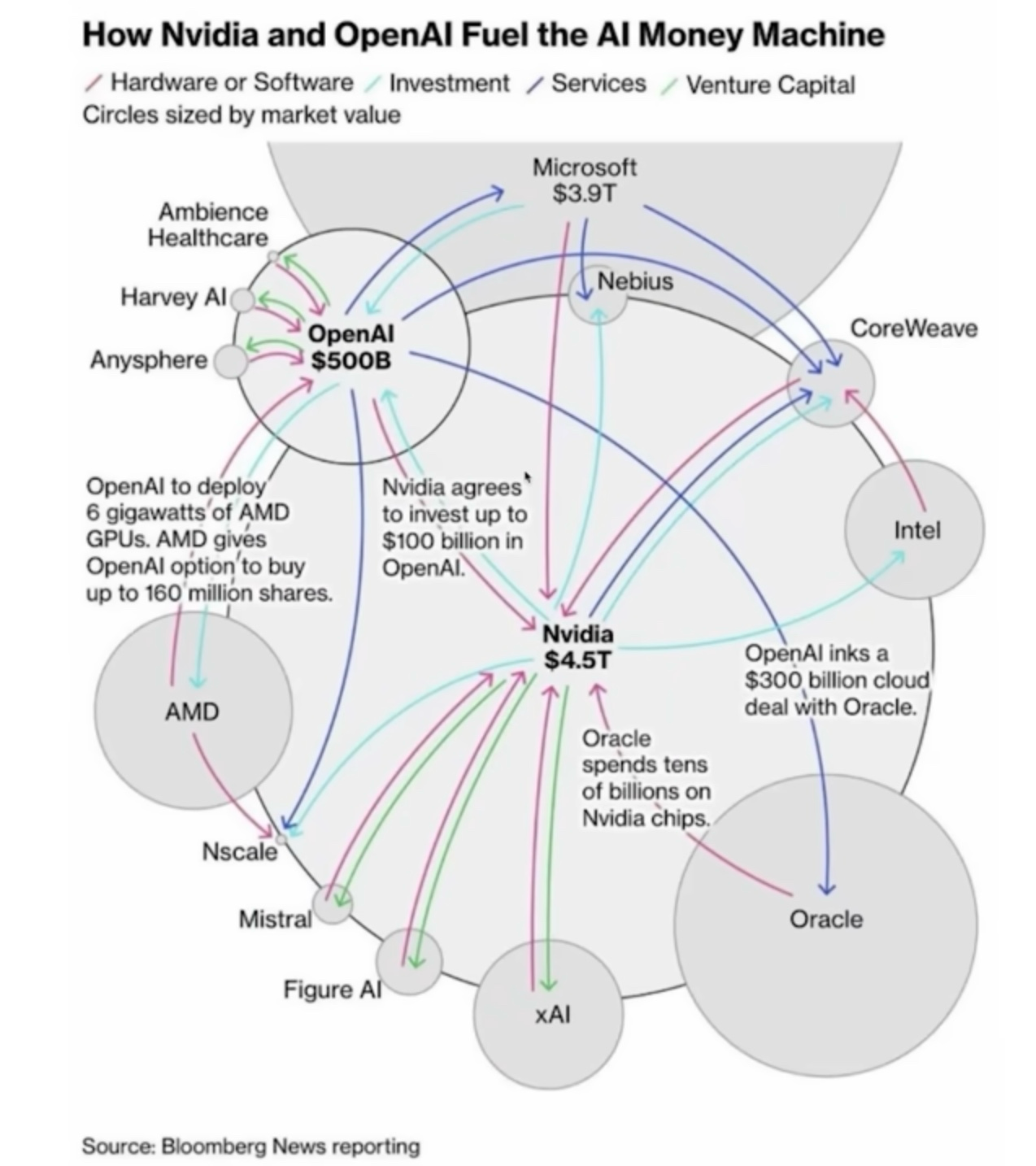

The core concern driving the bubble hypothesis is the highly concentrated nature of AI-related representation in the US stock market, restricted to a few major players: NVIDIA, OpenAI, Microsoft, Oracle, AMD, xAI, and indirectly, Intel.

The central figure in this group is NVIDIA, currently a multi-trillion-dollar company, thanks to its expensive, high-demand GPU chips. The debate revolves around whether the overwhelming demand for these processors is organic market-driven growth or if it is being artificially inflated through questionable financial arrangements. Suspicion leans toward the latter, based on a pattern of significant investment loops between suppliers and customers.

Case Study: NVIDIA and OpenAI

NVIDIA has invested a colossal sum—reported to be in the $100 billion range—into OpenAI.

Despite its estimated value of around $500 billion (home to ChatGPT and Sora), OpenAI has relatively tiny revenues of approximately $12 billion (not profit) and continues to operate in the red.

In a striking deal, OpenAI then contracted with Oracle for an estimated $300 billion in computing services.

To fulfill this massive contract, Oracle is building a mega datacenter and, in turn, purchases tens of billions of dollars worth of GPUs from NVIDIA.

This mechanism triggers the alarm: a supplier invests in a customer so that the customer can purchase products from the supplier itself.

While similar investments from venture capitalists (VCs) are common, a supplier-to-customer investment creates a closed loop that muddies the waters.

With this system in place, it muddies the waters, making it so we cannot definitively say if the massive demand for GPUs is actually market-driven or artificially sustained by this quid-pro-quo, which keeps the stock prices of these companies and the cost of GPUs artificially high.

Similar scenarios exist across the AI ecosystem:

NVIDIA and CoreWeave: NVIDIA sells a huge volume of GPUs to the datacenter company CoreWeave to build its computing facilities. NVIDIA then contractually rents these very computers back. Furthermore, if CoreWeave cannot secure enough external contracts, NVIDIA agrees to buy the chips back. This arrangement effectively de-risks the entire investment for CoreWeave.

NVIDIA and xAI: A similar reciprocal relationship is observed between NVIDIA and xAI.

NVIDIA, Microsoft, and Nebius: Microsoft secured 100,000 GB200 GPUs from NVIDIA (a deal worth $33 billion), and then pays Nebius—an AI datacenter company in which NVIDIA has invested—for AI services that utilize those very chips.

OpenAI's Venture Arm: OpenAI Venture Arm invests in companies like Anysphere, Harway AI, and Ambience Healthcare, which then become customers purchasing services from OpenAI.

Considering these highly suspicious deals and the vast amount of capital poured into AI that has yet to generate commensurate, visible value, the fear of an AI bubble appears more than legitimate.

The question, therefore, is inescapable: is the demand for these AI services truly organic?

The uncomfortable answer? Likely not.

Let’s dig into it.

The Return on Investment (ROI) and Execution Problem

The major critics of the AI surge are currently pointing to a fundamental lack of expected ROI and productivity gain from the technology. Prestigious voices, including MIT researchers and IBM CEO Arvind Krishna, have weighed in.

Generally, all criticism revolves around the flawed business models surrounding AI adoption.

Insights from MIT: High Adoption, Low Gains

The main takeaway from an MIT report is a feeling often summarized by the FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) syndrome: businesses jump onto the AI bandwagon out of necessity, often purchasing expensive CUDA licenses (NVIDIA's software platform) and instructing engineers to "do something with it."

What's fundamentally missing is a clear, planned path: what product will be created to generate revenue, and how will AI accelerate that goal? Because the investment required to even be a player in this space is colossal, this missing clarity is particularly impactful.

The MIT report highlights several critical issues:

Adoption is high, gains are low: An earlier MIT study found that over 90% of companies claim to use AI, yet 97% reported little to no measurable productivity improvement. Their observation is that "everyone is experimenting, but nobody is scaling."

The Execution Problem: AI is fully capable of automating meaningful work. However, most companies lack clarity on task-level viability, process redesign, and workflow ownership. This is an execution failure that kills ROI before it even begins.

Top Performers Rebuild Around AI: Companies seeing real gains do one thing differently: they treat AI as a core operating infrastructure. They redesign roles, restructure teams, and rebuild processes to let AI handle repeatable tasks while humans focus on judgment and decision-making.

The consequence of poor deployment is massive: failed rollouts increase error rates, slow down teams, and can cause delays. MIT notes that companies that botch early AI adoption often pause all efforts for 12–24 months due to internal distrust.

The Astronomical Cost of AI Infrastructure

Beyond the execution challenge, IBM CEO Arvind Krishna's analysis focuses specifically on the ROI of the infrastructure required to support and scale the AI world, centered on datacenters and software licensing costs.

The Datacenter Economics Problem

We already have multi-gigawatt datacenters operating today (e.g., Meta's Altoona Data Center at 1.4 GW, and the Princeville Data Center in Oregor at 1.3 GW), and tech giants are planning future facilities approaching 100 GW.

According to publicly available numbers and the IBM CEO's analysis, a new 1 GW AI-native datacenter will cost an estimated 80 billion USD, including operational expenses. To repay the loan for such a project, the data center would need to generate approximately $8 billion in annual profit.

But what makes up this estimated $80 billion cost?

Let's break it down:

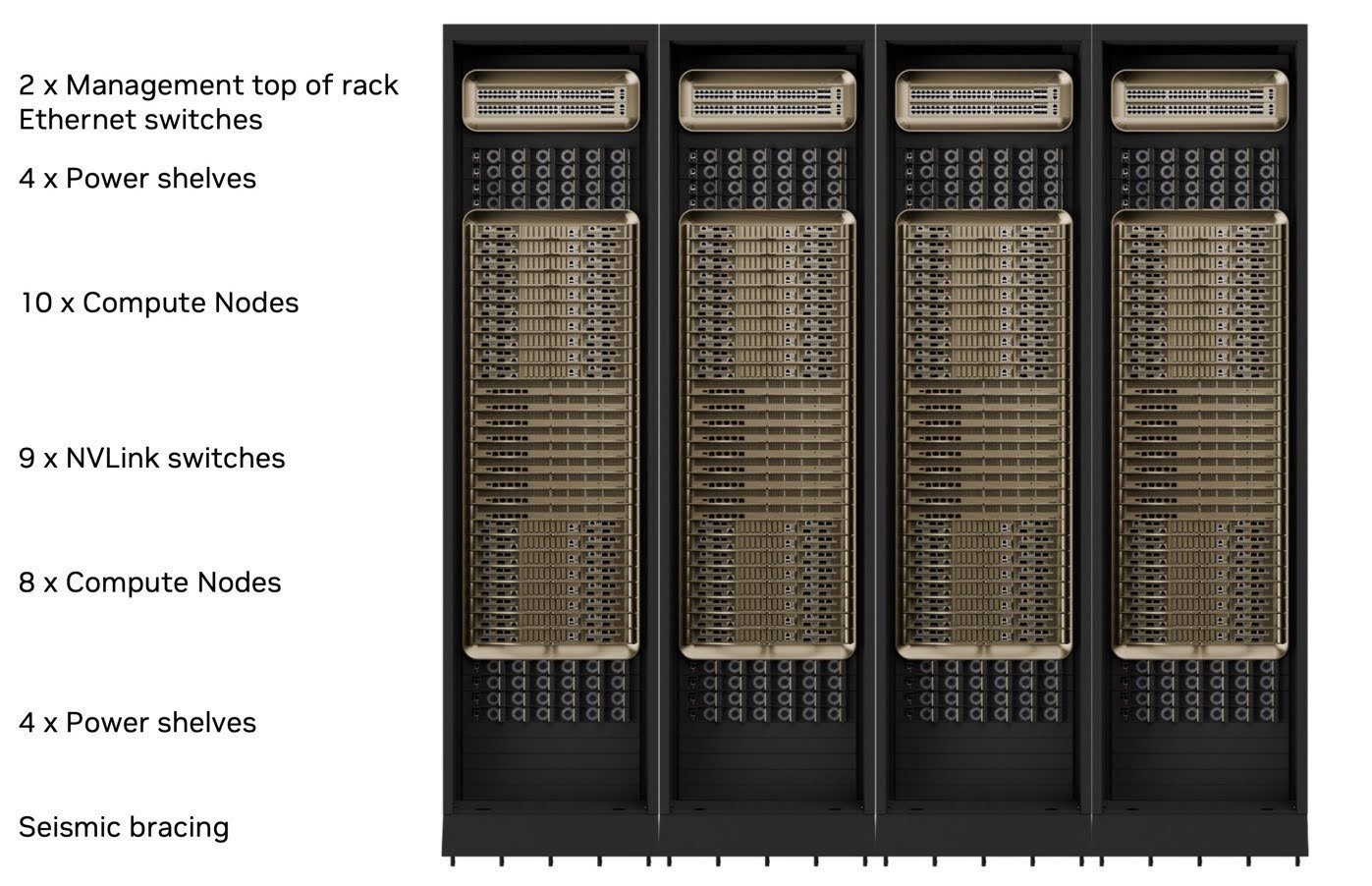

4 DGX racks

Basic Compute Unit: NVIDIA defines a basic NVIDIA Scalable Unit (SU) which includes eight DGX GB200 NVL72 racks and all necessary networking, storage, and cooling. This unit requires about 1.2 MW of power.

Rack Cost: A single, fully loaded GB200 NVL72 rack (with 72 GB200 superchips) costs approximately $3 million due to the high price of a single B200 GPU (about $30,000 to $50,000 when bought in bulk orders of 100).

Total Rack Cost: Simple math shows that a 1 GW facility could theoretically fit about 830 SUs (1 GW / 1.2 MW). Meaning: 830 SUs x 8 racks/SU x $3million/rack = about $20 billion just for the DGX racks.

Basic Compute Unit Layout in One Row

Adding the cost of auxiliary hardware (high-speed networking, liquid cooling management), the physical infrastructure (power buses, fiber, AC), and ongoing operational costs makes the $80 billion estimate both reasonable and realistic.

The Depreciation Burden

On top of the initial investment, a critical burden is the rapid depreciation of GPUs. New models are released every few years, and customers always demand the latest and greatest processors, leading to a typical refresh cycle of only 3–5 years. Replacing such a massive, multi-billion-dollar investment in such a short period presents a huge financial challenge to any viable business model.

A significant reduction in infrastructure cost is clearly necessary for a sustainable business model. Personally, I believe this requires a serious competitor to NVIDIA's GPUs to drive prices down, as well as a greater push to find cheaper, performance-equivalent alternatives in model design, similar to the approach seen with China’s DeepSeek (read more about that in my article here).

The Hidden Cost: Software Licensing

While hardware is a major expense, we must not overlook the software cost.

NVIDIA's CUDA software platform has been an incredible accelerator for its ecosystem. With it, engineers can freely develop their application or agent in C, C++, Python, Fortran, or MATLAB and compile it for any NVIDIA GPU model and AI cluster configuration. It takes care of the GPU-specific architecture by transcoding the original source code so that it is optimized for the highly parallel computational characteristic of any target devices. However, it is not cheap.

NVIDIA's enterprise solutions for licenses—such as for virtual GPUs or AI Enterprise—can cost up to $4,500 per GPU per year, as can be seen in their Enterprise Licensing Guide. For a relatively small project involving a team of 100 developers deploying on a 100-GPU cluster, the annual licensing cost alone could reach $45 million.

But what are the alternatives?

Currently, a serious alternative to CUDA is lacking.

Google offers its Tensor Processing Unit (TPU), specialized for its proprietary TensorFlow framework. The major difference is that while NVIDIA sells hardware for businesses to install themselves, Google primarily offers its own datacenters with installed TPUs for rent.

In both models, businesses are highly dependent on one of two providers. Small to mid-sized businesses often must rent GPU cycles from cloud providers, which offers a flexible but still expensive alternative, subject to resource availability.

The Imminent Correction of Expectations

The adoption of AI and the resulting technological transformation are, as we have argued, inevitable. However, the path to mass adoption is currently obstructed by three major, interconnected flaws that, taken together, suggest a significant market correction—a bubble burst—is likely imminent.

First, the current ecosystem is dangerously reliant on circular investment loops. When a supplier (NVIDIA) must heavily finance its customers (OpenAI, CoreWeave) to generate massive orders, the demand for its core product (GPUs) is structurally compromised. This system creates a spectacular, multi-billion-dollar feedback loop that sustains valuations and high component costs, yet masks the true, independent demand from the wider market. If the external market falters or the vendor financing stops, the entire edifice of inflated stock prices collapses.

Second, this inflated demand directly feeds the unsustainable economics of AI infrastructure. The astronomical capital expenditure of $80 billion for a single 1 GW datacenter, driven largely by proprietary, high-cost GPU hardware and expensive software licenses like CUDA, simply does not generate a viable Return on Investment (ROI) under current pricing models. The criticism from MIT and IBM is clear: a technology with a 97% failure rate for measurable productivity gains cannot support a multi-trillion-dollar infrastructure buildout. The current trajectory is one of massive spending and unproven returns, which is the very definition of speculative excess.

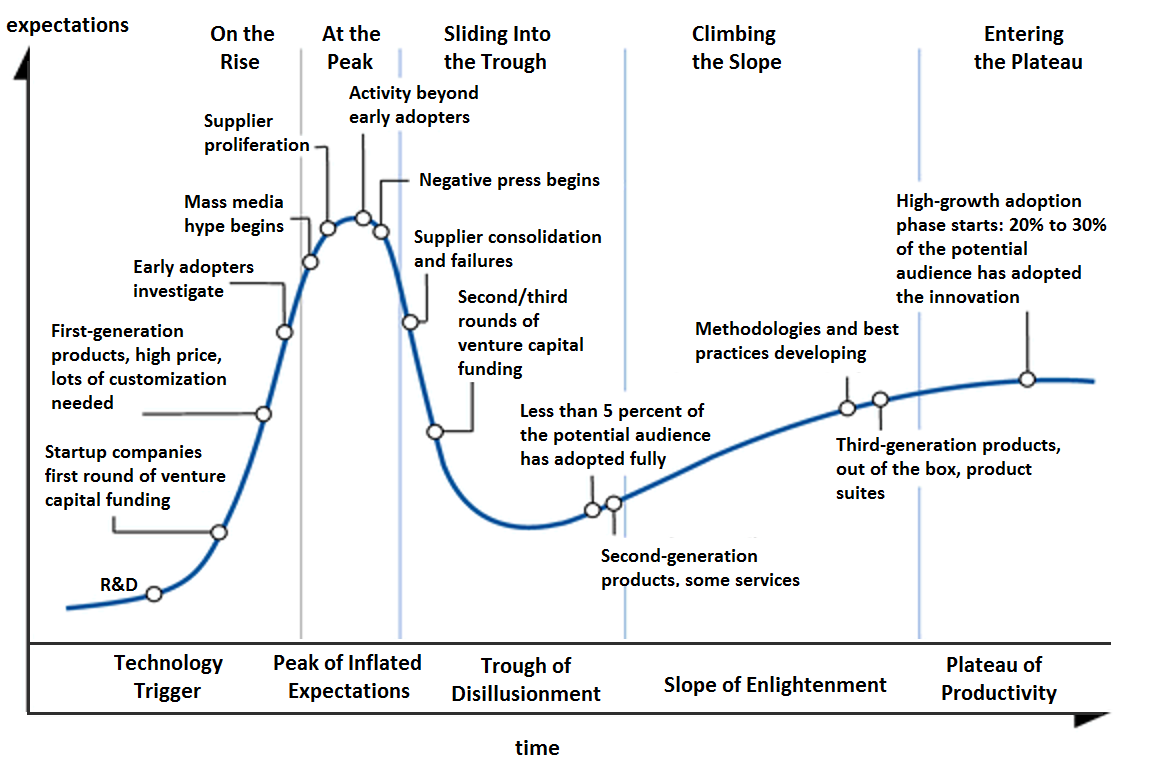

Finally, and perhaps most critically, the market is mismanaging the human element. The fear of missing out (FOMO) has driven companies to invest without a coherent business plan, resulting in the Execution Problem and a severe gap between adoption and actual productivity gains. This failure to integrate AI thoughtfully, coupled with the inevitable social disruption from job redesign, places a heavy burden on governments and businesses. The initial phase of any disruptive technology is marked by chaos and inflated expectations, as illustrated by the adoption curve. The current, massive distance between our soaring expectations and the measurable, profitable reality is the exact gap that defines a bubble.

The AI technology itself is real, but its current valuation is based on the assumption of frictionlessly exponential growth and universal, immediate profitability—an assumption that the financial loops, infrastructure costs, and ROI failures prove to be false.

The coming correction will not signal the end of AI, but the end of irrational AI exuberance. It will be the necessary correction that wipes away the improvisers and forces the survivors to focus on sustainable business models, driving down costs (likely through competition to NVIDIA) and successfully implementing the critical workflow redesigns needed to realize genuine value.

The development and deployment of intelligent systems are unstoppable, but for the revolution to be beneficial rather than financially devastating, the market must first navigate the difficult, corrective phase that these alarming economic and operational signals clearly portend.

The Inevitable Social Impact and the Path Forward

Every truly disruptive technology typically follows a predictable adoption curve. Initially, expectations are high amid rapid adoption. As the technology moves into real-world products, skepticism grows, and expectations temper to a more realistic level, resulting in a temporary dip. This "saddle point" sees the initial improvisers drop out, and the technology eventually flattens out into a widely accepted plateau, built on genuinely profitable products.

A large gap between the peak of initial enthusiasm and the final, stable plateau is characteristic of a bubble, and the bigger this gap, the higher the rate of failure and the more severe the social repercussions on employment.

By Olga Tarkovskiy - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=27546041

The Employment Challenge

Automatable Jobs: MIT estimates that nearly one in eight U.S. workers perform tasks that AI can already automate (~12% of U.S. jobs).

Job Architecture Redesign: The true disruption is not widespread job disappearance, but the redesign of most roles. MIT projects that up to 70% of current job descriptions will undergo task-level changes as AI absorbs routine work.

The development, deployment, and adoption of AI are inevitable, but the process will not be painless. The social impact will be the most critical challenge. Governments have a key role to play in creating and deploying proper policies to help businesses assist with the transition and retrain the workforce accordingly.

Looking Ahead: The Fully Automated Future

What I believe is still missing is the critical combination of robust AI models with truly intelligent robotic entities to realize the full potential of this technology. My projection is a future factory operating 24x7x365 without need for illumination or human climate control, manufacturing products in a fully automated fashion, with humans remotely monitoring the process.

As we are beginning to see great progress in "intelligent" robotic developments, we may not be far from the first proof-of-concept of a fully automated factory. I will continue to monitor this area and report on future developments.